Growing up, I was both encouraged to learn about women’s history through biographies and historical fiction. As the 1990s brought moderate progress in telling racially diverse stories, I began to understand how the abolition, women’s suffrage, civil rights, and feminist movements were intertwined. However, those stories never included mention of sapphic, gender non-conforming, or trans women.

This women’s history month, I am revisiting biographies of women who were included in the 1996 Scholastic Encyclopedia of Women in the United States, one of the most frequently read books on my childhood bookshelf. All of these individuals are held up as iconic women in U.S. history, though I never knew were part of the LGBTQIA+ community until my adulthood.

Harriet Hosmer (1830 – 1908)

Harriet Hosmer defied gender expectations by following her passion for sculpting, becoming an influential figure in the Neoclassical style.

Throughout her childhood, Harriet was encouraged by her father to be independent and curious, as well as partake in athletic activities like hiking, swimming, and fishing. She attended Sedgwick School for Young Ladies, a progressive school notable for teaching proper anatomical terms. As her passion for sculpting grew, she enrolled in medical school to better understand the human body for her art. At the time, less than one percent of women would go to college and Harriet would become the first woman to receive an anatomy certificate from Missouri Medical College.

In 1852, she would travel to Rome, where she would live for most of her life, to work with other renowned artists and breakaway from the gendered confines of American society.

At the age of 29, she revealed the work she is most widely known for, Zenobia in Chains, at the 1863 International Exhibition at London’s Crystal Palace. Critics accused her of not being the authentic sculptor, disbelieving that a woman could produce such a work. In fact, she would sue several publications for libel after they continued to discredit her work.

Harriet would continue to be drawn to mythological and historical female characters who represented strength and independence, providing a social commentary on the role of women in the 19th Century.

At the time, her perspective was viewed solely through a feminist lens, but a closer look reveals a more sapphic message, especially as she was not heavily involved in women’s rights activism until later in her life. Throughout her life, Harriet had long-term relationships with woman, going so far as to refer to herself as “Hubby” of her long-term partner Louisa Ashburton, whom she called “Sposa.” Her lifelong attraction to women was documented throughout her letters and journals.

Throughout her life, Harriet would present in gender non-conforming ways, keeping her hair in a bob before it was in fashion and wearing men’s clothes. Further, she would travel without a chaperone despite being unmarried, which was scandalous at the time.

In her later years, as Neoclassical sculpture came out of popularity, Harriet would focus on innovating machinery and processes to support the field of sculpture.

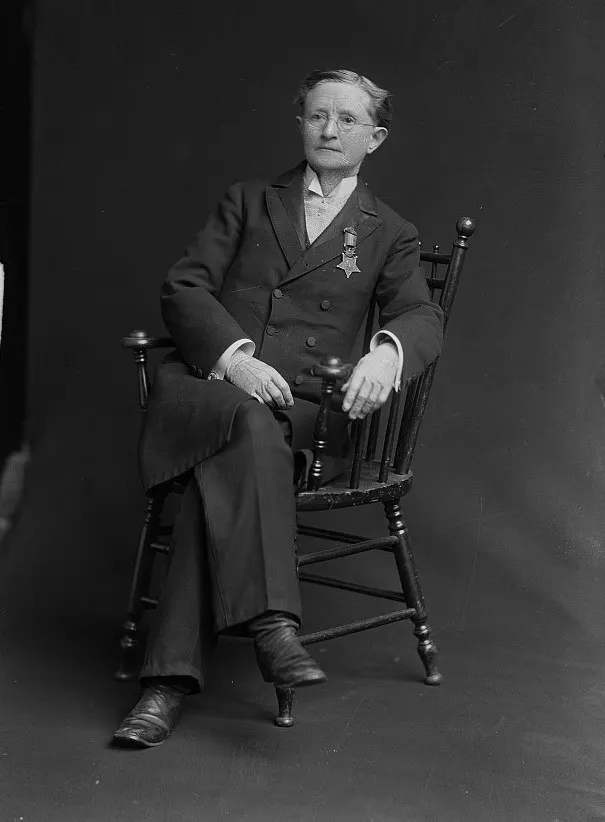

Mary Edwards Walker (1832 – 1919)

Mary Edwards Walker was smart, committed, and unapologetically queer.

Mary was born in 1832 to a parents committed to the abolition of slavery and liberation of women. Throughout her childhood, Mary was encouraged to learn, follow her curiosity, and engage in intellectual debate. Her parents allowed her to wear “bloomer” pants, when most women were confined to skirts and corsets.

The Walkers founded the first free school in Oswego, New York, where their daughters were encouraged to study the same material as male students. All children were expected to help out on the farm, eliminating any sense of gender difference between daughters and sons.

Mary went on to Falley Seminary and was a teacher while saving money to enroll in medical school. She received her medical degree from Syracuse Medical College in 1855, making her the second woman to graduate from the school with such a degree.

After graduation, Mary married Albert Miller and they opened a medical practice. The endeavor was short-lived as patients were not accepting of a female doctor and the couple would divorce due to his unfaithfulness.

When the Civil War broke out, Mary was barred from serving as a medical officer because of her gender assigned at birth. She would become a volunteer nurse at temporary hospitals throughout Virginia. By 1863, her application to serve as an army surgeon was finally accepted and she became the first female U.S. Army Surgeon. Throughout this time, she would wear pants, considered men’s clothing at the time, citing that they made her more comfortable and were more conducive to surgery.

During the war, she was captured by the Confederate Army and held prisoner at Castle Thunder for four months. She would refuse a female prison uniform. Upon release, she continued to serve at the Louisville Prison Hospital and an orphanage. Her contributions were recognized with the Medal of Honor for Meritorious Service, but she did not receive a military pension as she was not considered an official army commission. In 1916, she would be stripped of her medal as the government determined she was not eligible. However, she continued to wear her medal for her entire life. President Jimmy Carter would reinstate her medal, posthumously, in 1977.

After the war, Walker’s eyesight began to fail and she began advocating for women’s rights full-time. She would be arrested numerous times for dressing like a man. Despite her commitment to the movement, she was largely ostracized from the women’s suffrage movement due to her gender expression, perceived as a stubborn refusal to conform to gender norms. She would continue to advocate for “dress reform” throughout her life and cultivate a community of others who were discriminated against for not conforming to gendered attire.

While there are no surviving letters or journals offering insight into Mary’s identity, her consistent, persistent male attire alludes to the fact that she may have been trans masculine. Further, throughout her life, she would live with other women also committed to women’s suffrage and dress reform without further context. Her autobiography Hit (1871) and medical manual Unmasked (1878) indicate feelings of oppression due to gender and explicitly outline sexual repulsion that could be interpreted as lesbianism, asexuality, or gender dysphoria as a woman. Nonetheless, Mary’s commitment to dress reform echoes in today’s movement for transgender inclusion and gender non-conformity.

Louisa May “Lou” Alcott (1832-1888)

While Louisa May Alcott identified as a woman throughout her lifetime, therefore included in this article, there is considerable evidence in her journals, letters, and stories that she may have identified as transmasculine if she lived at another point in history and experience sapphic attraction.

Throughout her life, her family referred to her with the more masculine nickname “Lou” with surviving letters referring to her as a “son” or “brother.” She would reflect that she was born with “a boy’s spirit under [her] bib and tucker” and would journal about wanting to be a man into her adulthood. Notably, in one of her last interviews in 1884, she was quoted, “I am more than half-persuaded that I am, by some freak of nature, a man’s soul put into a woman’s body.” When asked why, she replied, “Well, for one thing, because I have been in love in my life with ever so many pretty girls, and never once the least little bit with any man.”

Lou’s seminal novel Little Women is among the most well-known books in the United States and beyond. Despite the title, the novel explores the myriad ways to experience womanhood, including the confines of the gender binary.

Lou Alcott grew up in Concord, MA to parents immersed in the transcendentalist movement. Her father, Bronson, was a thought leader among the likes of Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Nathaniel Hawthorne. However, his approaches to his work and mental health struggles led to uncertain finances for the family.

As the second eldest daughter, Lou would take on several jobs in order to support the family, including as a seamstress, governess, teacher, and nurse. As an avid writer, she would sell her poetry, novels, and short stories as well. Over the course of her life, she would publish over 250 stories, poems, and serials, spanning from gothic thrillers to children’s fables to personal accounts.

Lou never wanted to write a novel for young women, as she did not feel well-equipped to relate to them. However, at her publisher’s request, she drew on stories of her childhood which would become Little Women.

Lou was committed to abolition, women’s suffrage, and prison reform throughout her life. Much of her writing, including Little Women, explores feminist themes of liberation. Though she is remembered as a literary spinster, Lou’s lack of husband and children may be attributed to her queerness. However, when her sister May died, she adopted her niece, and when her eldest sister’s husband passed, she took pride in “being a father to these children.”

In her middle age, Lou struggled with mental health and illness, possibly due to mercury poisoning used during her recovery from typhoid fever as a young adult, and passed away at the age of 56.

Frances Perkins (1880 – 1965)

The workers’ rights we benefit from today are grounded in the legacy of Frances Perkins.

Long before she was the first woman appointed to a presidential cabinet, Frances was born and raised in New England by a socially conservative family, spending summers in Newcastle, Maine and winters with her grandmother in Worcester, MA. Frances began studying physics at Mount Holyoke College, the oldest higher education institution for women in the country. However, a visit to local mills during an economic course introduced her to the need for labor reform. Though her family expected her to return home and work as a teacher until she was married, after graduation, Frances relocated to Illinois, volunteering at Hull House where her passion to labor reform and women’s suffrage was further fueled.

Frances would study Sociology and Economics at the Wharton School and then Columbia University, earning her a Masters Degree at a time when few women had a degree of any kind. Due her time at Columbia, Frances work at settlement houses, which allowed her to live and work alongside the low-income, largely immigrant, community.

After graduation, Frances was involved in labor organizations, such as the Consumers League and the Committee on Safety of the City of New York. She was integral in lobbying New York state legislature in limiting working hours for women and children, particularly in light of the catastrophic Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire. She was an eyewitness to the disaster.

Frances continued to play a pivotal role in labor reform in the state of New York, including as Industrial Commissioner under then Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt. It is no surprise that when we became president in 1933, he would also appoint her as Secretary of Labor. This role came at a critical time as the country crawled out of the rubble of the stock market crash of 1929 and was deep into the Great Depression. As Secretary of Labor, Frances oversaw the development of Social Security benefits and national labor reform through the Fair Labor Standards Act which established unemployment benefits, workplace safety regulations, child labor restrictions, minimum wage, and the forty-hour work week. Due to her contributions to the development of the U.S. Employment Service and public works projects, many claim that she was the primary architect of FDR’s “New Deal.”

Backlash was inevitable, however, and she was charged with protecting communists by the House Un-American Activities Committee. Accusations grounded in homophobia, sexism, and xenophobia were rampant but ultimately the Committee could not charge her with anything. President Roosevelt did not defend Frances and prevented other cabinet members from doing so. They would have further rifts due to her pacifist stance in the wake of World War II. Nonetheless, she retained her role as Secretary of Labor for eighteen years

In 1913, Frances married Paul Caldwell Wilson, though retaining her maiden name professionally. Work came first for both Frances and Paul, which strained their relationship. However, pregnancy difficulties and the birth of their daughter Susanna in 1916 kept them together. Shortly thereafter, Paul began experiencing erratic behavior, identified as “manic depression” at the time, and required care at institutions until his death in 1952. She did not discuss these challenges publicly.

Frances began a relationship with Mary Hartman Rumsey, whom she lived with in Washington, D.C. Mary was a social leader in her own right, founding the Junior League and serving as chair of the Consumer Advisory Board. Evidence documents a close, loving relationship that was likely romantic, though short-lived as Mary passed away in 1934. She would later share a home with U.S. Representative Caroline O’Day, who was a woman who loved other woman, but there are no letters, journals, or documents indicating the nature of their relationship.

Frances continued to serve during the Truman administration on the Civil Service Commission until 1952 and would lecture at Cornell University after leaving public office. She also published a bestselling biography of FDR, The Roosevelt I Knew. She enjoyed intellectual debate with students at the Telluride House, an academic living community, for many years before she passed away.

Bessie Smith (c. 1895 – 1937)

Bessie Smith is regarded as the “Empress of Jazz,” an iconic blues and jazz singer of the Harlem Renaissance, with a legacy that echoes through the music industry today.

Growing up in segregated Chattanooga, Tennessee, Bessie and her five siblings grew up in extreme poverty, raised by an aunt after her parents passed away within six years of each other. To help support her family, Bessie would perform on the streets, often accompanied by her brother on guitar. As young as 14 years old, Bessie’s talent was well-regarded, bringing her to the theaters throughout the South to perform, particularly notable for a young Black female singer at the time.

Bessie continued to perform on vaudeville stages, eventually coming under the tutelage of Ma Rainey. There is speculation that they were likely lovers during this time. By her mid-twenties, Bessie was performing solo acts all over the East Coast and landed a recording contract with Colombia Records.

Her moving version “Down-hearted Blues” catapulted her into the national spotlight. She would sell over six million records in less than five years, making her the highest paid Black entertainer of her time. With her fame, Bessie brought star power to the stage with glamorous costumes. Yet, by incorporating the realistic challenges of being a Black woman and the struggles of the working class into her music, she remained refreshing and relatable for audiences. Her songs and musical style would make audiences cry just as strongly as they would laugh.

It wasn’t only her musical talent that made Bessie a star. She was firmly an independent, liberated woman, smashing all stereotypes of femininity. She was known for love of drinking (which would land her in jail for disorderly conduct) and celebrating Black female sexuality. This included her own openness about her bisexuality in her music and documented trysts with many of her female backup dancers. Bessie was married to a man, Jack Gee, for six years, a marriage that ended due to their mutual infidelity, his raging jealousy, and his discomfort with Bessie’s bisexuality the demands of show business.

As the Great Depression hit the United States, Bessie’s recording career slowed but she continued to perform across the country. Her life was cut short in 1937 during fatal car accident. Over 5,000 people attended her funeral, celebrating the vivacious life of Bessie Smith. She was buried in an unmarked grave, as her ex-husband refused to pay for a headstone. As Bessie’s legacy lived on for decades, Janis Joplin and Juanita Green, whom Bessie had inspired in childhood, installed her headstone in 1971, which reads, “The Greatest Blues Singer in the World Will Never Stop Singing.”

Joan Baez (born 1941)

Joan Baez is a legendary name in contemporary folk music, known for using her platform to advocate for social justice.

Throughout her childhood in Los Angeles and Boston, Joan was active in local choirs. She enrolled in the theater program at Boston University, but ultimately dropped out to follow her love of singing. Her voice captured the attention of musician Bob Gibson who invited her to perform at the 1959 Newport Folk Festival when she was just 18. This performance landed her a record deal with Vanguard Records which would release her first album in 1960. Though traditional folk music was not popular at the time, the album reached the Top 20 charts and her next two albums would achieve Gold Record status.

With increasing fame, Joan did not hide her views on war and civil rights. She sang “We Shall Overcome” at the 1963 March on Washington before Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. would deliver his “I Have a Dream” speech. She was arrested numerous times for protesting the Vietnam Wat and would perform frequently at rallies that aligned with her viewed. While some celebrities might have been concerned that political action would affect their fame, Joan was unfazed and her music continued to be successful. She performed a powerful set at the 1969 Woodstock Festival

Many know of her intense relationship with then up-and-coming musician Bob Dylan, as well as her brief marriage to draft activist, David Harris. However, she was open about her relationship with a woman named, Kimmie, as early as 1973. The 2023 documentary I Am A Noise provided an intimate look into the life of Joan Baez. She reflected on her relationship with Kimmie as a “major turn” that “gave [her] another whole angle on love.”

Joan’s recording career and activism continued for decades, including alongside Cesar Chavez and the rights of migrant workers, marching with the Irish Peace People, and protesting the Dakota Pipeline at Standing Rock. She stopped touring in 2019.

Well into her eighties, Joan continues to write poetry and paint. Her autobiographical collection of poetry When You See My Mother, Ask Her to Dance was published in 2024, sharing memories of her childhood. Joan was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2017 and received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Latin Grammys in 2019, cementing her legacy as an influential folk musician, committed to equity around the world.

Sandra Cisneros (born 1954)

Sandra Cisneros’ iconic novel The House of Mango Street is beloved, required reading in high schools across America, capturing the struggles and joys of young Latinas.

Sandra was born to Mexican immigrants in Chicago in 1954. Her family moved frequently between Chicago and Mexico City, never allowing her time to feel settled in one place. Further, as the only sister among six brothers, she felt isolated, turning to books for comfort. She was a quiet, reflective child, who wrote her first poem when she was ten. Her love of writing carried her through creative writing programs at Loyola University of Chicago and the University of Iowa.

In young adulthood, Sandra was a teacher and counselor, but continued to follow her passion for creative writing. Her first collection of poetry, Bad Boys, was published when she was just 26, but the following year, she would publish her most notable work, The House on Mango Street. The work was informed by her own experience as a Mexican-American and the experiences of her students at the Latino Youth Alternative High School, which supported youth who had dropped out of public school. She felt there was no literature that amplified the Latin-American experience, especially for those who lived in poverty.

Despite the fact that book was recognized with the 1985 American Book Award, Sandra did not experience overnight success. She would continue working multiple jobs and moving frequently in order to find an accepting community. She finally settled in San Antonio, Texas, finding kinship among artists who had similar experiences of living at the cultural intersection of Mexico and the United States.

Throughout this period, she continued to publish poetry, novels, short stories, and children’s books, many of which were critically acclaimed throughout the nation. She would also participate in numerous prestigious scholarships and fellowships. Through her MacArthur “Genius Grant” Fellowship in 1995, she founded Los MacArturos, which build community among other MacArthur Fellows who identity as Latino. Barack Obama recognized her contributions to Latino art and culture with the National Medal of Arts in 2016. Gender plays a critical role in much of her work and Sandra publicly identifies as queer

Throughout her career, Sandra has been deeply committed to community, especially supporting other writers and Latino artists. She has shared that her decision not to have children stems from her dedication to writing and mentoring young artists. This has spawned initiatives like the Macondo Foundation, which workshops for aspiring writers. She continues to use her art to amplify the experiences of women of color, giving voice to a community that is often overlooked.

A Note on Language

Many of the individuals documented in this article identified as women during their lifetime. While many experienced love for others who identified women, expressed discomfort in being female, and/or would wear masculine clothing by choice (not necessity), few were living during a time where the concepts, let alone language, of being lesbian, transgender, or nonbinary were accessible. Because of this, unless the individual prefers other language, the word “sapphic” is used to describe people who lived as women and had romantic or sexual relationships with women, “transmasculine” for people assigned female at birth who consistently discussed wanting to be a man, and “gender non-confirming” for people assigned female at birth whose gender expression was not distinctly feminine and/or expressed some consistent, persistent, insistent feelings of not being a woman.

Presented in partnership with Boston LGBTQ+ Museum of Art, History & Culture

Harriet Hosmer: Mathew B. Brady & Studio, American (Warren County, New York active 1844 – 1895 New York, New York), Harriet Goodhue Hosmer, 1857. Salted paper print, hand-colored with black ink. Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Transfer from Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard College Library, Bequest of Evert Jansen Wendell

Mary Edwards Walker: Dr. Mary Edwards McCaw wearing her Medal of Honor.

C.M. Bell, photographer. Walker, Dr. Mary. [Between 1873 and 1916] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress.

Louisa May Alcott: Notman, James, “Louisa Alcott,” Digital Public Library of America, https://dp.la/item/86a0b69d881ede0609c5478d9bedf4b1. Courtesy of The New York Public Library.

Frances Perkins: Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins at her desk, ca. 1938. National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD.

Bessie Smith: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Joan Baez: Gotfryd, Bernard, photographer. Joan Baez at Anti-draft demonstration, Central Park, Bandshell, NYC. New York United States New York State, 1968. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2020737842/.

Sandra Cisneros: Sandra Cisneros in 2019. Nick Simonite. Texas Monthly.

Sources:

Alexander, Kerri Lee. “Biography: Mary Edwards Walker.” National Women’s History Museum, 2019. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/mary-edwards-walker.

Alexander, Kerri Lee. “Biography: Sandra Cisneros.” National Women’s History Museum. Accessed March 11, 2025. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/sandra-cisneros.

“Bessie Smith.” National Museum of African American History and Culture. Accessed March 11, 2025. https://nmaahc.si.edu/lgbtq/bessie-smith.

Chaiklin, Harris. “Perkins, Frances: The Roosevelt Years.” Social Welfare History Project, 2012. https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/eras/great-depression/perkins-frances-the-roosevelt-years/.

Cisneros, Sandra. “About My Life and Work.” Sandra Cisneros. Accessed March 11, 2025. https://www.sandracisneros.com/mylifeandwork.

“Discovering Frances Perkins.” The ILR School, February 24, 2009. https://www.ilr.cornell.edu/news/about-ilr/discovering-frances-perkins.

Dolkart, Andrew S. “Frances Perkins Residence.” NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, July 2023. https://www.nyclgbtsites.org/site/frances-perkins-residence/.

Doyle, Emily. “‘I Write about People Whose Lives Are on Fire’: A Conversation with Sandra Cisneros, by Emily Doyle.” World Literature Today, April 4, 2022. https://worldliteraturetoday.org/blog/interviews/i-write-about-people-whose-lives-are-fire-conversation-sandra-cisneros-emily-doyle.

Ermac, Raffy. “Joan Baez Talks Meeting Her Girlfriend Kimmie in This New ‘I Am a Noise’ Clip.” Out Magazine, October 14, 2023. https://www.out.com/film/joan-baez-documentary.

Gomez Rhine, Manuela. “Queer Artist, Queer Courage.” The Huntington, June 16, 2021. https://huntington.org/verso/2021/06/queer-artist-queer-courage.

Gustin, Melissa. “‘the Queerest, Best-Natured Little Chap Possible.’” National Museums Liverpool. Accessed February 25, 2025. https://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/stories/queerest-best-natured-little-chap-possible.

“Harriet Goodhue Hosmer: Artist Profile.” National Museum of Women in the Arts, May 29, 2020. https://nmwa.org/art/artists/harriet-goodhue-hosmer/.

“Harriet Hosmer (1830-1908), Neoclassical Sculptor.” Mount Auburn Cemetery. Accessed February 25, 2025. https://www.mountauburn.org/notable-residents/harriet-hosmer-1830-1908/.

“Her Life.” Frances Perkins Center. Accessed March 11, 2025. https://francesperkinscenter.org/learn/her-life/.

Hill, Terina. “Bisexual Blues Singer Bessie Smith and the Royal Theater.” Philadelphia Gay News, February 11, 2020. https://epgn.com/2020/02/11/bisexual-blues-singer-bessie-smith-and-the-royal-theater/.

Hunt, Dennis. “Joan Baez Raising Her Voice Again.” Los Angeles Times. June 14, 1987. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1987-06-14-ca-6960-story.html.

Katz, Jonathan Ned. “Mary Edwards Walker: November 26, 1832-February 21, 1919.” Out History, August 8, 2024. https://outhistory.org/exhibits/show/gender-benders/mary-edwards-walker.

Lawrence, Wade, and Scott Parker. “Joan Baez: 50 Years of Peace & Music.” Bethel Woods Center for the Arts. Accessed March 11, 2025. https://www.bethelwoodscenter.org/news/detail/joan-baez-50-years-of-peace-music.

Levy, Arthur. “Bio Info.” Joanbaez.com, April 2024. http://www.joanbaez.com/bio/.

“Louisa May Alcott.” American Battlefield Trust. Accessed February 25, 2025. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/louisa-may-alcott.

“Louisa May Alcott.” The New York Public Library. Accessed February 25, 2025. https://www.nypl.org/node/5656.

Mahon, Maureen. “How Bessie Smith Influenced a Century of Popular Music.” NPR, August 5, 2019. https://www.npr.org/2019/08/05/747738120/how-bessie-smith-influenced-a-century-of-popular-music.

Mathias, Kelly, and Lauren Curtwright. “Voices from the Gaps: Sandra Cisneros.” Regents of the University of Minnesota, October 7, 2004.

Norwood, Arlisha R. “Louisa May Alcott.” National Women’s History Museum, 2017. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/louisa-may-alcott.

Pass, Alexandra R., and Jennifer D. Bishop. “Mary Edwards Walker: Trailblazing Feminist, Surgeon, and War Veteran.” American College of Surgeons, 2016.

Queirós, Carlos J. “Sandra Cisneros Still Inspires Hispanic Writers 25 Years after ’mango …” AARP, Spring 2009. https://www.aarp.org/entertainment/books/info-04-2009/the_joy_of_words.html.

Queirós, Carlos J. “Sandra Cisneros, Author of ‘House on Mango Street,’ Reflects on Writin…” AARP, April 1, 2009. https://www.aarp.org/entertainment/books/info-04-2009/sandra_cisneros_house_on_mango_street_25th_anniversary.html.

Rios, Carmen. “Rebel Girls: Bessie Smith Was a Queer Pioneer, and We’re Finally Gonna Get to Talk about It.” Autostraddle, May 22, 2020. https://www.autostraddle.com/rebel-girls-bessie-smith-was-a-queer-pioneer-and-were-finally-gonna-get-to-talk-about-it-283712/.

Salvo, Victor. “Frances Perkins.” Edited by Owen Keehnan. Legacy Project Chicago. Accessed March 11, 2025. https://legacyprojectchicago.org/person/frances-perkins.

Thomas, Peyton. “The Radical Acceptance behind ‘Little Women.’” Oprah Daily, June 22, 2022. https://www.oprahdaily.com/entertainment/a40395357/the-radical-acceptance-behind-little-women/.

Thompkins, Gwen. “Forebears: Bessie Smith, the Empress of the Blues.” NPR, January 5, 2018. https://www.npr.org/2018/01/05/575422226/forebears-bessie-smith-the-empress-of-the-blues.

“The Unconventional Life of Harriet Hosmer.” Street Art Museum Tours, September 22, 2023. https://streetartmuseumtours.com/blogs/blog/the-unconventional-life-of-harriet-hosmer?srsltid=AfmBOoripnYYhVGfZxsuLE9fumCKI6_0UlWUcRT3NeBH38-0M98TWdN8.