Queer people have always existed.

Black LGBTQIA+ icons have always been powerful agents of change, challenging societal norms and paving the way for future generations.

Yet, the stories of Black queer individuals are often the hardest to uncover as largely White, wealthy accounts were documented and preserved.

However, these six icons capture the experience of queer Black folx from the post-Civil War Era through the Harlem Renaissance and Stonewall Riots to today. As we celebrate their legacies, we also honor the voices that history has yet to fully acknowledge.

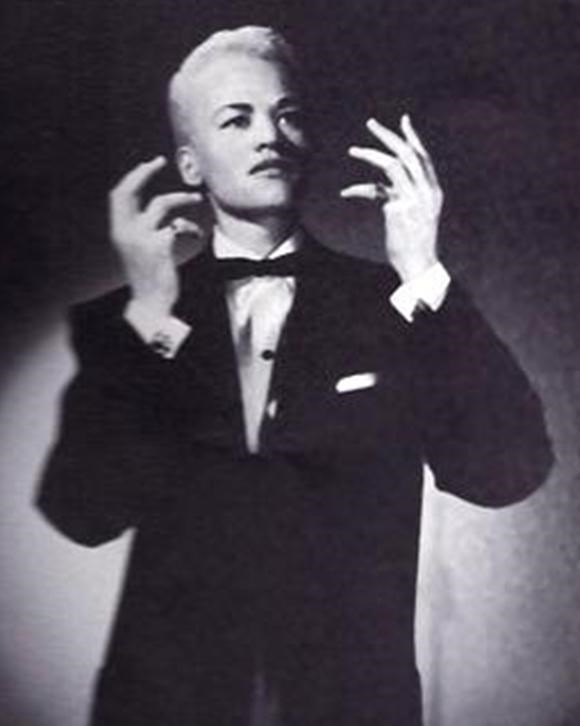

Stormé DeLarverie (1920-2014)

Stormé DeLarverie was a biracial, queer, drag king who was a force for representation on stage and inclusion in the streets.

Born Viva M. Thomas to a wealthy white man and his Black servant, Stormé never knoew her birth parents and was raised by foster parents. As a child, she experienced violent bullying due to, not just being Black, but being biracial. One incident would leave her with a lifelong limp from being hung by her leg from a fence post.

However, growing up in New Orleans, Stormé was immersed in jazz. Her distinctive baritone voice brought her to stages at New Orleans clubs by age 15. Her talents would take her across the country and to Europe, as well as into the Ringling Brothers Circus.

By 1955, she had moved to New York City, where she would live the rest of her life. With her partner Diana, she produced the Jewel Box Revue, the country’s first racially integrated drag show with Stormé as the sole drag king.

Stormé was arrested frequently for not dressing as her gender assigned at birth, though sometimes she would be detained while wearing feminine clothing by police who thought she was a drag queen.

Legend has it, in fact, that she was the “mysterious butch lesbian” who was arrested at the Stonewall Inn on June 29, 1969, inciting the infamous riots.

Throughout her life, Stormé was known for her fierce protection of the Greenwich Village queer community, particularly ensuring youth and lesbians were safe. Formally, she was a bouncer at lesbian clubs; informally, she would patrol the streets with a pistol.

“You don’t do ugly around me,” she said in 2002, as her nightly neighborhood rounds continued into her eighties. “Just don’t try it. You’re apt to wind up with your ass on the floor.”

Close friends recall that Stormé never identified as a lesbian and once lived as “husband and wife” with Diana, making it possible that she may have identified as nonbinary or trans-masculine if she were alive today.

Diana died in the 1970s and Stormé would live the rest of her life alone, though cared for by close friends.

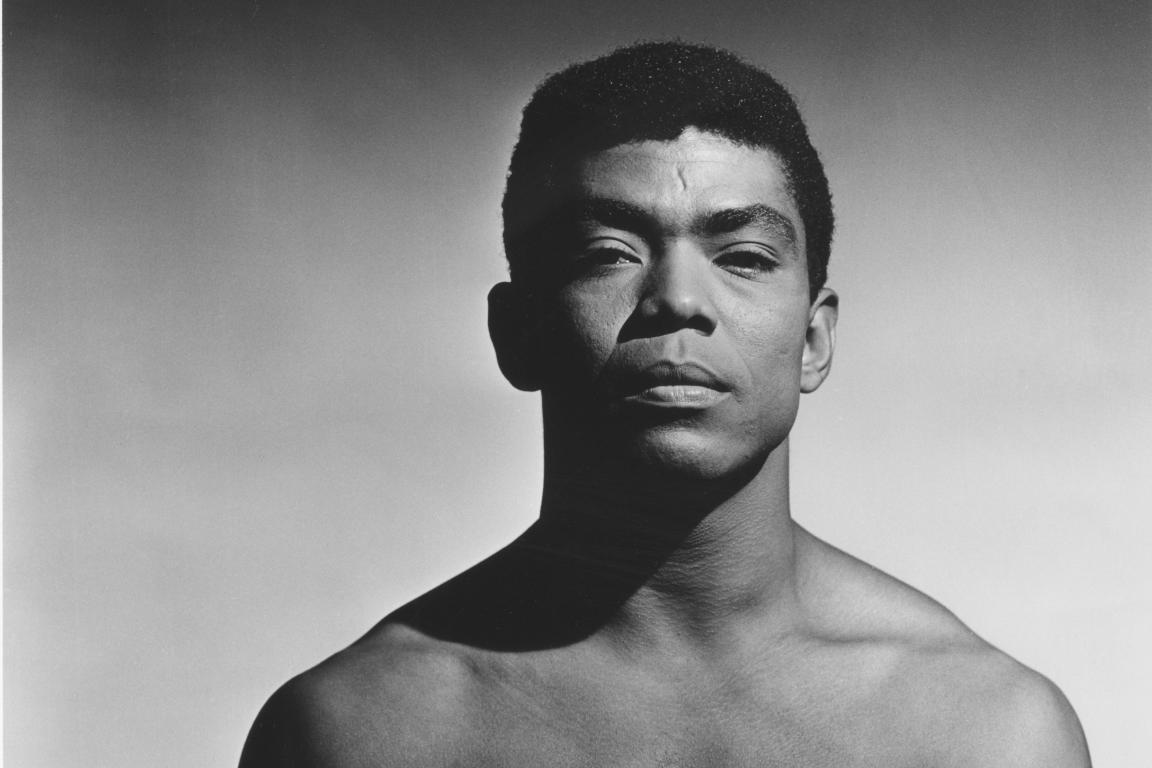

Alvin Ailey (1931-1989)

Alvin Ailey is one of the most iconic names in dance with a legacy that continues to inspire some of Broadway’s best.

Born into extreme poverty in Texas, Alvin was captivated by the Black joy experienced at church, despite his community’s challenging position. He would purse dance as an avenue to experience and demonstrate that unique joy.

His family moved to Los Angeles when he was 11, but it wouldn’t be until he was 18 that he discovered his love of dance through the multiracial studio of Lester Horton.

In 1958, he founded the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, still in operation, as a company that centered the Black experience through ballets grounded in Alvin’s lived experience as a Black gay man. His company welcomed dancers with talent and ability to tell a captivating story, regardless of formal training, which set his work apart from other, largely white, troupes.

Later, his work would move to address the global struggles of Black folx through his productions, including apartheid South Africa. His contributions to the arts and Black culture earned him recognition from the Guggenheim, NAACP, United Nations, National Museum of Dance Hall of Fame, and numerous more.

Over the decades, Alvin would expand his work to include dance schools and additional ensembles that focused on arts education for under-resourced communities.

Alvin would pass away due to AIDS-related complications in 1989.

Miss Major Griffin-Gracy (born c. 1940)

Miss Major Griffin-Gracy has been a champion of transgender and intersex inclusion, especially for women of color and incarcerated trans folx.

Growing up in Chicago, her parents assumed her desire to be a woman would be something she would grow out of. However, as a teenager, Miss Major met a drag queen named Kitty who introduced her to the queer community, allowing Miss Major to recognize herself as a transsexual woman (the preferred term at the time).

In her young adulthood, Miss Major would present publicly as a male. However, in college, her roommate discovered her female clothing and she was expelled.

By 1962, she was expelled from another college and moved to New York City, where she engaged in sex work, as many trans women had to, and continue to have to, to survive.

She was active in the drag scene, performing as a showgirl. Miss Major was present at the 1969 Stonewall Uprising.

In 1970, she was arrested due to an altercation with a client and served time in prison. During this time, she was put into the mental hospital of the prison, presumably because being transgender was percieved as a mental illness at the time, where she experienced hehumanizing abuse at the hands of the guards. This experience would galvenize her commitment to prison reform for trans people.

As the AIDS Crisis swept the queer community, Miss Major provided direct care to those in need in New York City, including her partner Joe Bob. After he passed, Miss Major would relocate to San Francisco, leading the transgender drop-in center and coordinating the city’s first mobile needle exchange program.

From 2004 to 2025, Miss Major continued her activism as Executive Director of the Transgender, Gender-Variant, and Intersex Justice Project, which supports incarcerated queer folx. She also founded and continues to lead House of gg, which retreat in Arkansas for transgender people of color.

Her love and support for young queer people and drag performers earned her the nickname “Mama Major.”

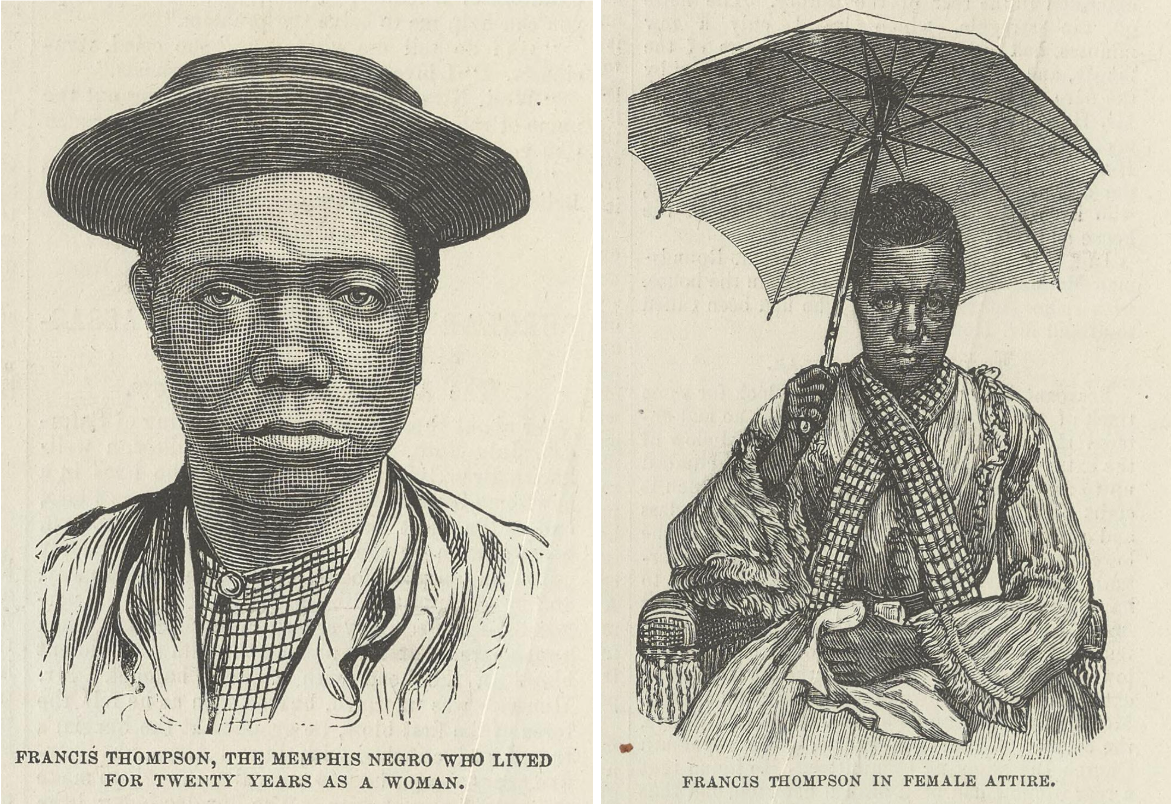

Frances Thompson (c. 1840 – 1876)

Due to the cultural moment and queer visibility of the Harlem Renaissance and post-Stonewall Era, most LGBTQIA+ Black narratives come from the past century. However, Frances Thompson takes us into the Civil War Era.

Frances was born into slavery in Maryland and moved to Memphis, Tennessee by her enslaver as a child. Though assigned male at birth, she expressed desire to live as a girl, which was supported by her enslavers. From a young age, she used a cane due to cancer in her foot that caused her legs to grow crooked.

Upon emancipation, her enslavers had been killed by the Union Army and she rented a home on Gayso Street in Memphis.

In May 1866, white police officers harassed a group of Black people, including children and Union Army veterans, who were having a party. Many revelers refused to disperse and arrests were attempted, escalating into three days of violence, including rape and arson, by white mobs. During “The Memphis Massacre,” at least 45 Black people were killed, in addition to nearly 300 more victimized, and arson destroyed 4 Black churches, four Black schools, and 91 homes and businesses.

Frances was one of the survivors of the Massacre. She was invited to testify to Congress against the white aggressors who had raped her, making her likely the the first transgender woman to do so.

The Memphis Massacre, including Frances’ testimony, would be critical in passing legislation to protect newly emancipated Black Americans. Specifically, her and Lucy’s testimonies were used as examples of the racially-charged hatred the Black community was facing after Emancipation.

After the trial, Frances worked as a seamstress and washerwoman, as well as practiced Hoodoo. She took in a new roommate, who was chronically ill.

As a Black transgender woman in the Reconstruction Era, she experienced similar prejudices as those who would come after her. She was arrested on several occasions for fighting, disorderly conduct, and operating a brothel, a common charge used against single Black women. In 1876, she was arrested for “crossdressing,” which was used as an example to discredit the emergent Black civil rights movement.

Frances was imprisoned among men, forced to wear masculine clothing, and sentenced to one hundred days on the chain gang, as she could not pay the $50 fine. The police shared her photograph with other cities to prevent her from living as a woman in other communities. The police and newspapers made a mockery of her and crowds would flock to the chain gang’s route to harass her.

She would contract dysentery shortly after her release and die within a few months.

Frances left an important legacy in her testimony of The Memphis Massacre, which would contribute to how the Reconstruction Era sought to protect newly emancipated Black people. She also stands as an example of the Black trans experience during the Civil War Era. Two other Black trans women, Anne “French Mag Porter” Casey and Jenny Smith, were arrested for crossdressing in Memphis as well. Though disregarded as copycats by the newspapers at the time, they more accurately depict the reality that the Black trans community has always existed.

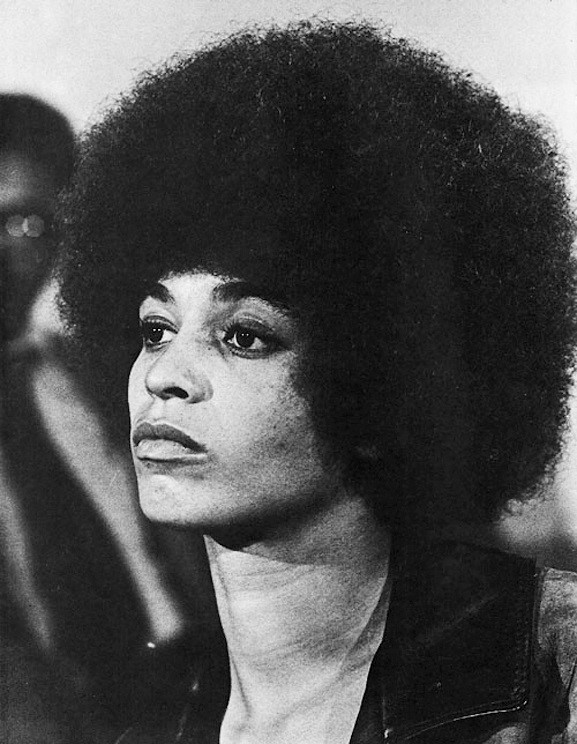

Angela Davis (born 1944)

Angela Davis was born in Birmingham, Alabama, one of the most racially segregated cites in the country. Her mother was an active member of Black civil rights organizations at the time, many of which were grounded in communist principles. In high school, these values were reinforced when she had the opportunity to spend a year going to school in the progessive New York City neighborhood of Greenwich Village.

She spent some time in Germany, completing a PhD in philosophy, before returning to the United States and begin her activist career.

She championed Black Civil Rights and the feminist movement as part of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Black Panther Party, and Communist Party. She was specifically focused on building connections between all marginalized communities, both in the U.S. but also in regards to Vietnam and South Africa.

In 1969, state Governor Ronald Reagan pressured the University of California at Los Angeles to fire Angela due to her political connections. This case was brought before the California Supreme Court, which ruled that political affiliation was not cause for termination. However, she was subsequently fired again for “incendiary” speeches.

At this time, Angela’s activism involved the Soledad Brothers Defense Committee. During this time, an armed gunman took several people hostage, demanding the Soledad Brothers be freed. Angela was charged as an accomplice because the gun was registered in her name.

Angela Davis was put on the FBI’s “10 Most Wanted” list for conspiracy, kidnapping, and murder and went into hiding for two months until she was arrested in New York City. The arrest was widely publicized, portraying Angela as a “dangerous terrorist,” and she was denied bail. She spent 18 months in solitary confinement.

Angela was ultimately acquitted of all charges, as the jury could not find any connection to the hostage scenario.

Upon release, Angela’s commitment for social justice was further fueled, especially for prison reform and the inequities caused by capitalism. She would continue to teach until 2008.

She continues to be a champion for social change, including Occupy Wall Street, Palestinian liberation, and Black Lives Matter.

Lorraine Hansberry (1930-1965)

The youngest and first Black recipient of New York Critics’ Circle Award, Lorraine Hansberry, was not public about her sexuality throughout her life. In fact, it was not until 2014, when her estate unsealed her personal writings, that her identity became known.

Lorraine is most well-known for her groundbreaking play, “A Raisin in the Sun,” which debuted on Broadway when she was just 29.

She was born to parents who active members of the Chicago Black community and committed to the social justice movements of the time. In fact, they were key in combating racist housing regulations at the Supreme Court level, suing the City of Chicago after they were pressured to relocate from a white neighborhood.

In adulthood, Lorraine would move to New York City and immerse herself in progressive journalism. She was a writer for Freedom, a Black newspaper, and, under a pseudonym for safety, The Ladder, the magazine for the lesbian organization, Daughters of Bilitis.

Lorraine was married to Robert Nemiroff, a white Jewish activist with similarly progressive views, for nine years. Though they would divorce, they remained close confidants. Robert’s financial security would allow writing to be Lorraine’s sole focus, including bringing “A Raisin in the Sun” to reality.

Though Lorraine would see her play become a globally acclaimed film starring Sidney Poitier, her life would be cut short by pancreatic cancer.

Presented in partnership with Boston LGBTQ+ Museum of Art, History & Culture

Sources:

“Day 5 – Stormé DeLarverie.” The American Black Story. February 5, 2025.

George, Nelson. ” Angela Davis. New York Times. October 19, 2020.

Klocke, Kirk. “Stonewall Veteran’s Wisdom on ‘Ugliness’ (audio recording).” 2009.

“Lorraine Hansberry.” Biography. August 23, 2023.

“Life Story: Angela Davis (1944- ).” Women & the American Story, New York Historical Society.

Rothsberg, Emma Z. “Lorraine Hansberry.” National Women’s History Museum.

“Transforming Dance around the World.” National Museum of African American History and Culture.