During the month of May, we elevate the stories of immigrants from the Asian continent and Pacific islands. Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander Heritage Month has been recognized in May across the United States since the 1970s, commemorating the arrival of first known Asian American immigrant from Japan, Nakahama Manjirō, on May 7, 1843 and the completion of the transcontinental railroad on May 10, 1896, a feat made possible by a considerable number of Chinese immigrants.

While the category “Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander” (AANHPI) was established in the 1960s to cultivate political power, it is important to recognize that the community is not a monolith and an umbrella term not embraced by all. Asian, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Island Americans represent people from a massive geographic region with diverse cultures and histories. This community includes 19 million Americans, 59% who are first-generation immigrants.

Throughout United States history, immigrants from Asia and Pacific Islands have made significant contributions to the country, while also facing systemic and interpersonal discrimination. In particular, Asian women experience fetishization, while Asian men experience emasculation or are perceived as asexual, making conversations surrounding gender identity and sexual orientation particularly fraught within the community.

To challenge these stereotypes and respect the diversity of the Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander community, we are uplifting the queer stories of AANHPI individuals to bring awareness to the intersectionality of race, gender identity, and sexual orientation today and throughout history.

Jiro Onuma (1904 – 1990)

During World War II, 120,000 Japanese Americans were sent to internment camps, a historical moment seldom mentioned in U.S. History classes. Jiro Onuma was one of those placed in an internment camp. Thanks to his personal papers and photos, donated to the GLBT Historical Society, we have unique insight into the experience of queer individuals in internment camps.

Queer identity in Japan had been quietly accepted since the 1600s. However, as Japanese immigrants integrated into the United States and homophobia among the white community became more rampant in the 1930s and 40s, similar anxieties emerged among the Japanese community.

As those sentiments evolved, Jiro immigrated to San Franciso from Yokohama with his father in 1923 at the age of 19. His father, Kogoro Onuma, was already living in California and returned home to retrieve his son after finding gainful employment at a laundry. Kogoro hoped the bring the rest of his family soon thereafter, but the 1924 “Johnson-Reed” Immigration Act would bar Asian immigrants’ entry to the United States and prevent the family from being reunited.

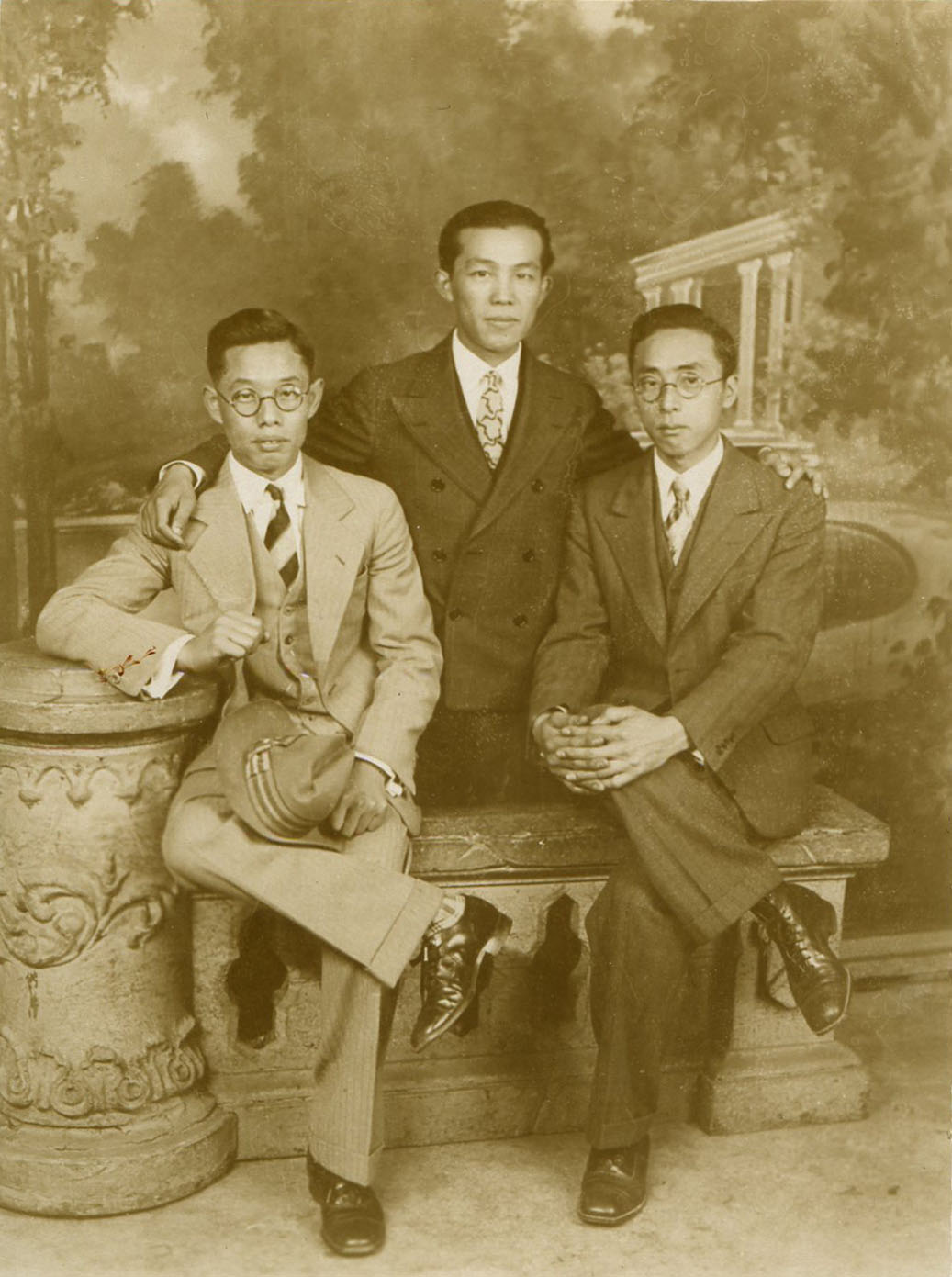

Like his father and other Japanese immigrants, Jiro worked in laundries. During this time, Jiro actively documented his life and there are many surviving photographs of his friends and boyfriends. He also collected homoerotic magazine and ephemera, including a bronze necktie shaped like a penis. He also had an extensive scrapbook of keepsakes and news clippings about Earle Liederman, a professional bodybuilder who offered mail-order athletic coaching.

Jiro remained unmarried throughout his thirties, when many other men would have begun starting a family. We know that he continued to live among other young single men in a bachelor community. They would play tennis, go to the seashore, and visit lavish gardens, museums, and mansions. His photos display an appreciate for fine things like luxury cars and trendy suits.

Following the U.S. entry into World War II and xenophobic hysteria following the attack on Pearl Harbor, virtually every Japanese American were placed into ten internment camps. 120,000 individuals with Japanese ancestry, including those who we born in the United States, were forced to leave their homes in the span of just a few days.

Jiro was sent to the Tanforan Assembly Center for five months, awaiting permanent relocation. Tanforan was a makeshift facility on a racetrack with hastily built barracks. Some people even slept in stables or converted grandstands. According the War Relocation Authority (WRA) files, Jiro likely waited twenty-five days before he was issued a cot and straw mattress.

On September 11, 1942, Jiro was transferred to the Topaz Internment Camp in Utah, nearly 700 miles from his home in San Francisco. Jiro worked in the prison’s mess hall for making nine cents (equivalent of $1.07) an hour, forty-four hours a week.

Topaz, like other internment camps, was organized into family units, rather than being gender segregated like most prisons. Historian Tina Takemoto hypothesizes that this may have been to promote the American norm of nuclear families among Japanese Americans. She notes that Japanese masculinity differs from the American concept of masculinity, so issues of gender and sexual orientation were front of mind for many Japanese American men of the era and would have been something a queer person like Jiro would be grappling with.

In photos from this period, we see Jiro showing physical affection to a man, likely Ronald, who is mentioned in his papers. These photos are the only know photographic evidence queer individuals in internment camps. The WRA kept thorough records of the internment camp experience, including photos, which is why we are able to know so much about the experiences of these individuals. This was partly in an effort to document Japanese Americans as “loyal citizens,” participating in mundane activities in the camps.

Same-gender intimacy certainly would not have been permitted at Topaz, as “offences against chastity, common decency and morals” were criminalized. Nonetheless, Roland and Jiro were able to have a relationship.

In Summer 1943, Ronald was sent to Tule Lake, a high-security facility for “disloyal inmates.” It is unclear exactly what prompted this, though we know that these transfers were frequently used as an intimidation tactic for individuals who expressed affinity to Japan. Ronald sent Jiro a photo of himself and a friend at Tule Lake, which Jiro kept among his possessions archive at the GLBT Historical Society.

Jiro was released on May 19, 1944 and would not reunite with Ronald. For just four days, he worked washing floors in Salt Lake City, before quitting and relocating to Denver, working as a bus boy. He returned to San Francisco in 1951, working as a house keeper. Jiro became a naturalized citizen in 1956.

Throughout his later life, Jiro enjoyed travelling throughout Asia and Latin America. He also befriended Peter Mycue, a man who had been stationed in Japan during World War II. Peter’s brother believe that Jiro was in love with Peter, but they remained platonic companions.

Jiro died in his studio apartment on June 27, 1990. Peter would find his body days after his death and, unfortunately, his home would be robbed shortly thereafter. Jiro left his estate to Peter, who would later donate his archives to the GLBT Historical Society.

Historian Tina Takemoto conducted extensive research into Jiro in 2009, giving us greater insight into his life and experience as a gay man in an internment camp. She published her research alongside an experimental film Looking for Jiro, a drag king imagining of Jiro’s life.

While Jiro was not the only queer Japanese American to be placed in an internment camp, his papers and photos are the most prominent accounts of being queer in the place and time. What we know of his live is symbolic of the LGBTQIA+ internment camp experience, representing dozens of other stories we may never know.

Esther “Brother Ha” Eng (1914-1970)

Esther Eng (née Ng Kam-ha 伍錦霞) was the fourth of ten children born to Chinese immigrants. Esther grew up in San Francisco’s Chinatown where she was exposed to a vibrant performing arts scene.

As soon as she was old enough to work, Esther found a job at the Mandarin Theater, which was known for bringing in the most prestigious performers from China. She was mesmerized by the world of the theater.

Esther wasn’t alone in her love of performing arts. In 1935, Esther’s father, Ng Yu-Jat, founded “Kwong Ngai Talking Pictures Company” to promote Chinese culture through film. Yu-Jat brought on his 21-year-old daughter as co-producer of the company’s first film, “Heartaches.”

“Heartaches” was likely the first “Cantonese singing-talking picture made in Hollywood,” centering a female protagonist in a romantic drama and starring opera star, Wei Kim Fong, whom Esther knew through the Mandarin Theater. At some point, Esther and Wei began a romantic relationship. It was also at this time that she would adopt the more Americanized name “Esther.”

With the success in the Chinese-American film market, Esther would then travel to Hong Kong with Wei to make her directorial debut in “National Heroine,” once again with Wei as the leading lady. Esther would stay in Hong Kong for three years, continuing to direct, write, and produced films that centered female protagonists. While romance films were popular, Esther also created films that explored issues of class, such as “It’s A Woman’s World,” which featured thirty-six female characters of distinct social status. Her work was recognized by the emerging feminist movement in China for promoting positive portrayals of women. However, as Chinese-Japanese tensions rose and a breakup with Wei, Esther headed back to the United States in October 1939 to continue filmmaking throughout World War II.

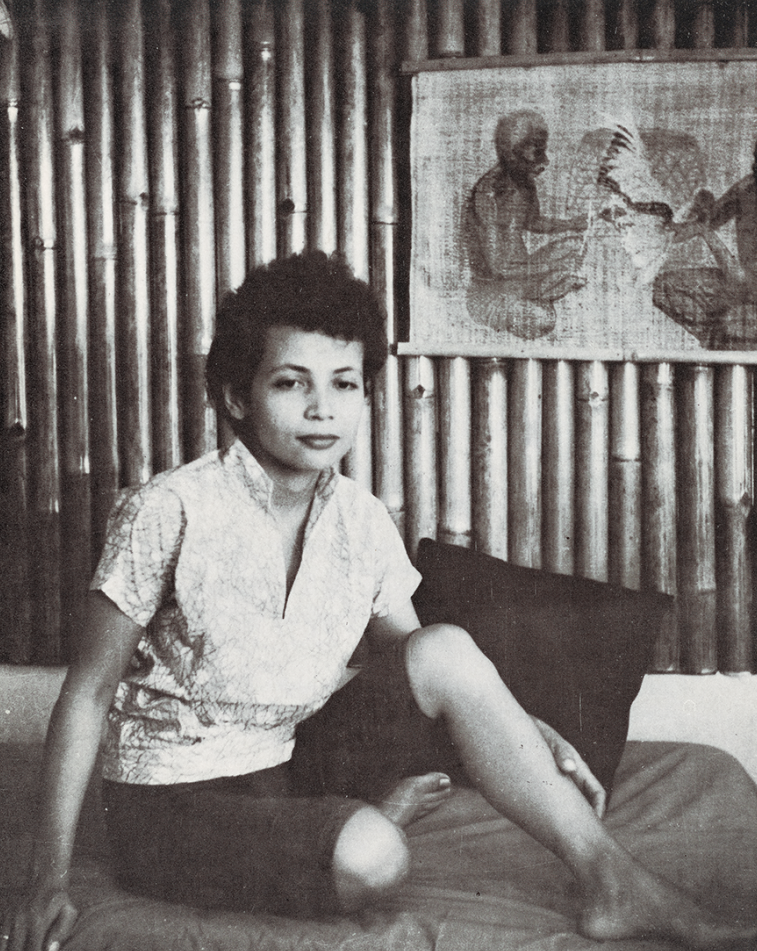

Throughout this time, Esther was open about her relationships with other women, though magazines would refer to her lovers as a “bosom friend” or “good sister.” She also adopted masculine gender expression, which may have earned her respect as an amateur in the male-dominated film industry, and insisted that people call her “Brother Ha.” This extended beyond dress, as one reporter put it, “It’s not just work, address, manner, and dress…it’s her sensibility that was completely that of a man.” Given this, it is possible she may have identified as transmasculine in modern parlance.

In addition, in the 1930s, China had lifted restrictions on women travelling abroad, making all female casts particularly in vogue. Many of these female actors would impersonate men in their performances, which may have made Esther’s masculine gender presentation less outstanding than in the 1940s and 50s. With the onset of the Cold War, the Lavendar Scare put pressure on LGBTQIA+ individuals to suppress their identities. However, Esther would not conform to these pressures.

When the Chinese Civil War ended in 1949, many Cantonese actors in the United States returned to China. Without the talent in the country and exorbitant filmmaking costs abroad, Esther’s writing and directing career came to an end, though she would be involved in distributing Hong Kong films to the States.

It was time for a change. After moving to New York City in 1950, Esther connected with Bo Bo, who led a Chinese acting troupe, some of the few we were not eager to return to the now-Communist China. Esther opened Bo Bo Café which employed these actors, providing them a steady income and the opportunity to learn English. Bo Bo’s was incredibly successful, with the New York Times saying, “At times it is next to impossible to obtain a table [but] the fare is worth waiting for.” With this success, Esther would go on to open four more restaurants across New York City over the next seventeen years, including Eng’s Corner, which was a known watering hole for gay men.

Esther passed away from cancer at the age of 55. Unfortunately, as her films were seldom distributed beyond Chinese-American cinema, only two of her ten films, “Golden Gate Girl” and “Murder in New York Chinatown,” survive, which has likely contributed to her relatively unknown status. However, Esther made enormous contributions to Chinese-American and Hong Kong cinema by telling complex stories and championing intersectional representation of Chinese and Chinese-American women.

Ger Van Braam (1927 – 2010)

Ger Van Braam was a Dutch-Indonesian woman who was the first lesbian to be featured on the cover of a U.S. lesbian magazine. While Ger never set foot in America, she was connected to lesbian fight for visibility and inclusion through The Ladder, specifically her correspondence with editor of the national Daughters of Bilitis publication. Her story represents the impact of the U.S.-based Daughters of Bilitis on queer women globally through an Indonesian lens, an important Asian and American connection in history.

Ger Van Braam was born to parents with Javanese, Spanish, and Dutch ancestry in Batvia (now Jakarta), Indonesian on August 31, 1927. Ger was always the “trouble-child” of the family’s nine children. She was an avid learner, studying art, law, and economics, but “restless” in deciding what her passions were.

During Ger’s childhood and adolescence, Indonesia experienced tremendous social change and conflict as the country fought for independence from The Netherlands and Japanese occupation. Her family would be placed in concentration camps twice, once in 1942 by the Japanese and subsequently in 1946, possibly, for their own protection as citizens with Dutch heritage. Ger’s father would pass away at some point during their first period in a concentration camp, though the cause is unreported.

The Netherlands recognized Indonesia’s sovereignty in 1949, recognizing anyone with Dutch heritage, such as Ger, living in Indonesia the opportunity to immigrant back to the country and gain Dutch citizenship. As a family of European and Dutch heritage, this decision was difficult. Three of her sisters, who had married men of European descent, decided to claim Dutch citizenship and move to The Netherlands. Others were tied to Indonesia and the family’s country estate. At 24, Ger solidified her Indonesian citizenship and remained in the country she had called home since birth.

Ger was aware that her attraction to women was not widely accepted. Around 1949, she married a man, who introduced her to lesbian novels like The Well of Loneliness and The Price of Salt, which brought her greater understanding of her attraction to women. (It is unclear if her husband introduced these books by chance or because of she expressed sapphic desire). The marriage only lasted three months. Her family was upset and confused by the separation, causing Ger to self-isolated from them for a year. This was around the time that Ger wrote her first story for The Ladder.

It is unclear how Ger came across The Ladder, the national magazine of the U.S. lesbian organization Daughters of Bilitis. In 1963, Ger’s first story “A Dope” was published, a semi-autobiographical essay about a shy young woman who is introduced to queer possibility by a flight attendant. Upon receiving the submission, Barbara Gittings, editor of The Ladder, was ecstatic. As a leader in the lesbian right movement and lifelong learner, Barbara encouraged Ger to continue writing for the magazine, as well as participate in research projects about LGBTQIA+ people and share stories about Indonesia as part of efforts to improve understanding and inclusion of lesbians in the United States and beyond. This relationship was particularly of note as Ger was the only subscriber from Indonesia.

Upon receiving such a reply, Ger felt validated and connected. Her subsequent letter to Barbara is vulnerable about her experience. She shares how isolated she feels as a queer woman in Indonesia with no community and few resources to understand her experiences.

“Novels and everything I read about ‘our people’ sound like fairytales to me;” she writes, “terrifying, fascinating, and wonderful.” She continues about the specific challenges of finding women with similar experiences, “In Djakarta, this city of millions, surely there are hundreds of my own sort -, women who are waiting, wondering, yearning, as I do? Then why can’t I find them, why are they so invisible, so concealed?”

In Ger’s experience, sexual fluidity among women of her age and social class was accepted, but few women willing to enter into a partnership. She felt that she was the there were no “gay women” other than herself.

Ger’s story would soon come true. The fleeting interaction with the flight attendant that had inspired her story would blossom into a friendship. Rora was a lesbian flight attendant who was knowledgeable about the queer subculture of Indonesia, predominantly gay men. Rora introduced Ger to the gay community. Both opening her eyes to the possibility of a more expansive, accepting world and solidifying her desire for a loving, monogamous relationship with a woman.

In late 1963 or early 1964, Ger would meet the then-married Hetty at a party. Their spark was immediate. Despite having a husband and son, Hetty also express her attraction to Ger. She willingly left her husband and gave up custody of her son to begin a life with Ger. They would secure a home together in Jakarta and declare themselves “married.”

Barbara and Ger would continue to correspond. For Ger, it is clear that The Ladder and her letters to Babara helped her connect to other lesbians and root her in a commitment to improving visibility in Indonesia. “If I had any inclination to leave this country and try my luck somewhere else,” Ger writes, “I am sure I don’t feel so any longer. I am sure there are more of our kind here, hundreds, thousands -, and I want to detect them and give them at least our friendship and understanding and the enlightenment they so badly need.” She permitted Barbara to publish their letters, which resonated widely with readers.

For Barbara, Ger’s detailed accounts of being queer in Indonesia reminded her of the global, transformative work of the Daughters of Bilitis. In 1964, Barbara asked Ger to be the first person to be featured on a photographic cover of The Ladder. Ger’s experience resonated with the readership across countries, as well as represented the need for inclusion globally. From a practical standpoint, as The Ladder was chiefly a U.S. publication, Ger’s standing as an Indonesian citizen would her and the magazine less at risk.

Ger agrees and would bestow the cover of the November 1964 issue of The Ladder. The issue would also feature the “Books for Ger” campaign to raise funds to send Ger and her growing queer community books about LGBTQIA+ issues. Ger would even send some to her sister, Mother Superior of a convent, to help her support young lesbians under her tutelage. Seeing Ger on the cover of The Ladder inspired other readers to have the courage to do the same despite the possibility of being outed and discriminated against in their daily lives.

In late 1964, Hetty, Ger, and their loyal friend Rora would move to The Netherland, as Hetty lost her Indonesian citizenship in her divorce and Rora had decided to repatriate. Rora’s decision may have been motivated by political corruption, growing tensions between Indonesia and Malaysia, and a period of hyperinflation across the country. This was a more difficult decision for Ger, who loved her life in Indonesia, but was devoted to her partner and friend, as well as understanding of the independence life in The Netherlands might afford her.

Ger reunited with Rora in 1964 and became a Dutch citizen in 1969. She worked as a secretary, accountant, and artist. It is unclear how long Hetty and Ger remained partnered. In 1985, Ger met Jooske, a partnership that would last throughout her golden years until Ger’s death in 2010 at the age of 85.

As a librarian, Barbara Gittings was committed to preserving history as it was happening. Her letters, including those from Ger, are preserved at the New York City Library.

Kiyoshi Kuromiya (1943 – 2000)

As an intersectional activist, Steven Kiyoshi Kuromiya played an integral role in the Black and LGBTQIA+ rights and anti-war movements, including supporting Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., founding the Gay Liberation Front in Philadelphia, and serving as a delegate to the Black Panther Party.

Kiyoshi Kuromiya was born in 1943 at Heart Mountain Concentration Camp in Wyoming to U.S. born Japanese Americans interned there. After released from Heart Mountain in 1945, the Kuromiyas relocated to Monrovia, California where Kiyoshi’s parents lived before World War II. As Kiyoshi was young at the time of internment, he did not recall that period, nor did his parents ever talk about it.

Kiyoshi was aware of his attraction to boys as young as 7 years old, as were his parents. As his parents encouraged him to be an avid learner, he had been given special permission to enter the young adult and adult sections of the library. Here, he discovered books like Alfred Kinsey’s Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, which introduced him to better understanding of sex and sexuality.

During this period, Kiyoshi was a target of other students. Puberty came early and his deep voice made him stand out, especially as one of few Asian American students in the predominantly White community of the suburbs.

He was arrested twice before his was 12 for lewd behavior with older teenagers. Kiyoshi explained, “My parents, of course, were very embarrassed and shocked and thought I would grow out of it.” The judge warned Kiyoshi and his parents that he was “in danger of living a lewd and immoral life” and was sentenced three days in juvenile detention.

This experience instilled a sense of shame in Kiyoshi, but also an acceptance that his interactions with other boys would need to be kept secret. This was compounded by the reality that queer people, especially gay men, were being arrested and tried by the House Un-American Activities Committee throughout the mid-1950s.

Access to information beyond reference books in the library was difficult, but Kiyoshi subscribed the Village Voice and LCE News throughout high school to learn what he could about the queer community.

In 1961, Kiyoshi moved to Philadelphia, where he would spend all of his adult life, to attend the University of Pennsylvania. Like many young people, he wasn’t sure what he wanted to study, but he received the prestigious Benjamin Franklin National Scholarship, which covered nearly all of his expenses at the Ivy League institution.

Being independent in a city allowed Kiyoshi greater access to gay community. However, Kiyoshi felt that many of the gay or affirming bars weren’t fun or safe. Many places were frequently raided. Few people of color could be found on the dance floor. In retrospect, Kiyoshi felt “a little bit unhappy about the idea that I had to seek social life in a bar.” However, the Penn campus and West Philadelphia at large had no LGBTQIA+ community, so it was the only option to meet other queer folx.

In the early 1960s, Kiyoshi was active in the civil rights movement and, later, anti-Vietnam War advocacy. He flew around the country to participate in protests. He even met Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and James Baldwin shortly after the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. He would join the 1965 Selma March, where he was beaten by a volunteer police at the state capitol building and hospitalized as a result. He was close to the King family and would care for MLK’s children during the week of their father’s funeral.

Locally, he organized anti-war demonstrations in Philadelphia as well, including the largest protest at the University of Pennsylvania where he threatened to burn a dog alive with napalm, symbolizing the impact on human lives in Vietnam.

In the mid-1960s, through the anti-war movement, Kiyoshi was connected to emerging LGBTQIA+ rights leaders like Clark Polak and Frank Kameny. He was part of the first Independence Hall Annual Reminder in 1965, one of the first demonstrations in the LGBTQIA+ movement. This was a small protest of about 40 people in front of historic Independence Hall. Among such a small, but visible group, Kiyoshi sees this as his public coming out.

As the LGBTQIA+ movement gathered momentum, Kiyoshi frequently participated in meetings and actions in New York City. During this period, a divide in the movement was forming between the assimilationists, individuals who believe in conforming to societal expectations, and radicals, like Kiyoshi, who wanted to disrupt the status quo. This led the Kiyoshi founding the Gay Liberation Front in Philadelphia.

Kiyoshi was committed to making sure that the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) was more reflective of Philadelphia’s LGBTQIA+ community, especially representative of the Black and Latino experience. However, it predominantly remained a group for gay men, believing that, as the Women’s Liberation Movement also gathered energy, it was important to focus on “male consciousness-raising” and combatting internalized homophobia and racism. This was a similar approach taken by the Black Panther Party, believing that people needed to be in touch with their feelings and identity in order to be effective activists.

Kiyoshi was inspired by Huey Newton and the Black Panther, as well as validated by his 1970 speech that acknowledged the Party’s alignment to the women’s and LGBTQIA+ rights movements.

GLF Philadelphia disbanded in as the needs of the Philadelphia community and overall LGBTQIA+ movement evolved. Kiyoshi continued working in the city, establishing the first gay organization on the Penn campus, Gay Coffee Hour, to foster social connection and political awareness among students and community members.

As the AIDS Crisis devastated the LGBTQIA+ community nationally, Kiyoshi was activated once again. In 1989, after being diagnosed himself, he founded Critical Path AIDS Project, which increased access to information in-print and online about HIV and AIDS at a time what the federal government refused to. He also founded the Philadelphia chapter of ACT UP. He was instrumental in the ten-year struggle with the FDA to approve protese inhibitor, Prixovan, serving at the only person living with HIV on the panel.

Kiyoshi continued to advocate for the wellbeing of people living with HIV throughout the 1990s, including the legalization of medical marijuana. Throughout his life, beyond activism, he was a food critic, world-ranked Scrabble player, practitioner of Kundalini yoga, and mentee of architect Buckminster Fuller. Kiyoshi passed away a day after his 57th birthday from AIDS-related complications and cancer. His archives are kept at the William Way LGBT Community Center in Philadelphia, documenting his tremendous contributions over thirty years to the civil rights, LGBTQIA+, anti-war, and HIV/AIDS movements.

Willyce Kim (born 1946)

Willyce Kim is the first out lesbian Asian-American writer to be published in the United States.

The first of three children, Willyce was born to second-generation Korean-American parents in Honolulu, Hawaii. She spent her childhood in Honolulu and San Francisco, and attended Catholic school.

Coming of age in the late 1960s, Willyce was inspired by activist artists like Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Adrienne Rich, and Diane Di Prime. She graduated from San Francisco College of Women (now University of San Francisco) in 1968 with a degree in English literature.

In 1970, she began working with Oakland’s Women’s Press Collective, which promoted written works about the female experience, including lesbians, tat a time when that was not socially acceptable and still considered a mental illness. However, the Collective was committed to creating safe spaces for women of all sexualities, races, and classes. Willyce travelled the country and hosting readings at colleges, independent bookstores, and bars, as well as connected with other activist poets like Audre Lorde and Pat Parker. During this time, she self-published her first poetry book, Curtains of Light.

Willyce was a naturally shy person. However, she recognized the importance of using her position as a published author to bring visibility to the Asian-American lesbian experience. She would continue to publish poetry and novels throughout the 1970s and 80s that centered lesbian identity, female empowerment, and colonialism. Her writing often incorporated food as metaphor with sensuality and humor.

“Kim’s lean, deadpan style belies her gift for seeing subtle humor in the ordinary, shambling state of human nature,” a critic wrote. “Her characteristic technique of breaking down the plot into brief scenes successfully conveys the sense that aimless events are converging into a mosaic of meaning, independent of the efforts of her anti-heroines and perhaps far beyond their ken.”

Willyce was influential for other queer Asian-American women, such as poet and artist, Kitty Tsui, the co-founder “Unbound Feet.” Upon coming out in the 1970s, Kitty recalled feeling unrepresented among white lesbians, Willyce was one of the only Asian-American lesbian role models, driving Unbound Feet’s commitment to bringing more visibility to this experience.

Willyce continued to be connected to West Coast lesbian and feminist publishing, working at the Doe Library at the University of California, Berkeley. She also hosted youth writing workshops in Oakland’s Chinatown. She would publish three collections of poetry, two novels, and be featured in numerous anthologies, always centering the lesbian experience with both authenticity and whimsey.

Arvind Kumar (born 1956)

Arvind Kumar never expected to be a champion of the South Asian LGBTQIA+ experience, but he has been integral to amplifying the intersectional identity of his community through Trikone.

Arvind was born in Varanasi, India, raised in rural Chhapra and Patna by loving but distant parents, a conservative Hindu grandfather, and supportive older brothers and uncles.

In post-colonial India, his family had hopes that Arvind would enter the Indian Administrative Services. However, Arvind’s strengths lay in math and science. Growing up, Arvind also knew that his attraction to other boys was not encouraged and often made one the target of aggression. In ninth grade, he began a secret relationship with a classmate. Though they tried to hide their relationship, other classmates observed their closeness and it became an open secret. Arvind even tried to convince his parents to become a boarding student, of course not sharing that this would allow him more time with his boyfriend. Arvind believes that because his boyfriend was a popular jock, they were spared from hostility.

In their senior year of high school, the boyfriend began blaming Arvind for seducing him. The relationship become physically and emotionally abusive, which Arvind could not share with anyone. His boyfriend tried to convince him that they needed to go to the same university, convincing that turned into harassment. The abusive relationship only ended when Arvind’s brother intervened at the train station, preventing the boyfriend from getting aboard and sending Arvind off to university.

Life at the prestigious Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur was better for Arvind, while healing from the trauma of the past year. He had a caring boyfriend who he says was his “first real happy love.” While the relationship ended, Arvind and the man are still in touch.

After graduating with a degree in engineering, Arvind moved to the United States for grad school. The first years in the U.S. were isolating. Arvind had difficulty making friends and connecting with other people in his program, as well disconnected from any LGBTQIA+ community and resources. He remained in the closet throughout grad school.

In 1982, Arvind secured a position at Hewlett Packard, which brought him to Silicon Valley. Living near the gay hub of San Francisco, Arvind attended his first Pride celebration and was proactive in connecting with a gay men’s group through which he began truly making friends, including other queer people of color. Through these connections, being gay no longer felt heavy and secret, as he met people experiencing queer joy and living openly.

In finding community, Arvind came out to his family to mixed reactions. His brothers were supportive, while his mother was distraught. However, she would eventually come around to accept her son’s authentic identity.

In 1986, Arvind met Suvir Das through the classified in The Advocate, his first friend who was both Indian and gay. As both Arvind and Suvir experienced difficulties finding community who understood the experience of being queer and South Asian, they began Trikone, a support group and newsletter.

In reflecting on his contributions to the South Asian-American queer community in 2021, Arvind reexplains, “I think I’m most happy about Trikone being able to be there for people at a time when there were few outlets. And it really stems from my own personal experience of feeling so alone and alienated and all locked up in my head for so long, for 30 years or 27 years, I lived that life. I didn’t want young people growing up at that time to feel so constrained.”

Trikone, meaning “triangle,” was sent to major gay publications across North American and India in order to gain membership. At a time when queer individuals were experiencing heightened discrimination due to the AIDS Crisis, Arvind published using his full name despite risk of being deported for doing so. Instead, he became a public figure in the LGBTQIA+ movement.

Around this time, he met Ashok Jethanandani, who would soon become his partner, who helped grow Trikone. Arvind left the engineering world in 1987 to dedicate his work to his community. He would go on to establish India Currents, an award-winning magazine about Indian-American culture in California. In the early years, Arvind would assemble the Trikone and India Currents magazine in the living room of the San Jose home he shared with Ashok. Ashok was involved as he could be, as well as financially supportive by being the sole income of the partnership in the early years of publication.

Eventually, India Currents and Trikone outgrew volunteer mailing parties at Arvind and Ashok’s home and moved to an office. However, the community involvement and personal correspondence with readers in the U.S. and India were crucial to the magazines’ impact.

“The main thing I got out of those letters was just the loneliness of having no one to talk to where you lived. And they needed to write to someone 10,000 miles away,” Arvind shared.

Ashok would add, “We would send a handwritten response back with almost every letter. Even if it was just a few words of support.”

Arvind would eventually turn over publication of Trikone to Sandip, who was a reader from India who become more involved when he came to the United States for grad school. Under Sandip’s leadership, Trikone was published more frequently with higher quality articles.

While Trikone stopped publishing in 2014, the newsletter inspired other queer South Asian organizations to organize across the country, many of whom embrace the Trikone moniker as a respected name in the community.

Arvind and Ashok were married in 1996 in an intimate Hindu ceremony. Arvind’s mother served as Sadhu, the holy person permitted to deliver the Hindu marriage rites. They remain close to their families with Ashok’s parents living with them for over 20 years and Arvind’s mother living with them for the final years of her life.

Presented in partnership with Boston LGBTQ+ Museum of Art, History & Culture

Esther Eng, Nanyang Film Studio, Kowloon, Hong Kong, 1938. Private Collection.

Ger, by Rora, 1963 as published in The Ladder, vol. 9, no. 2, November 1964.

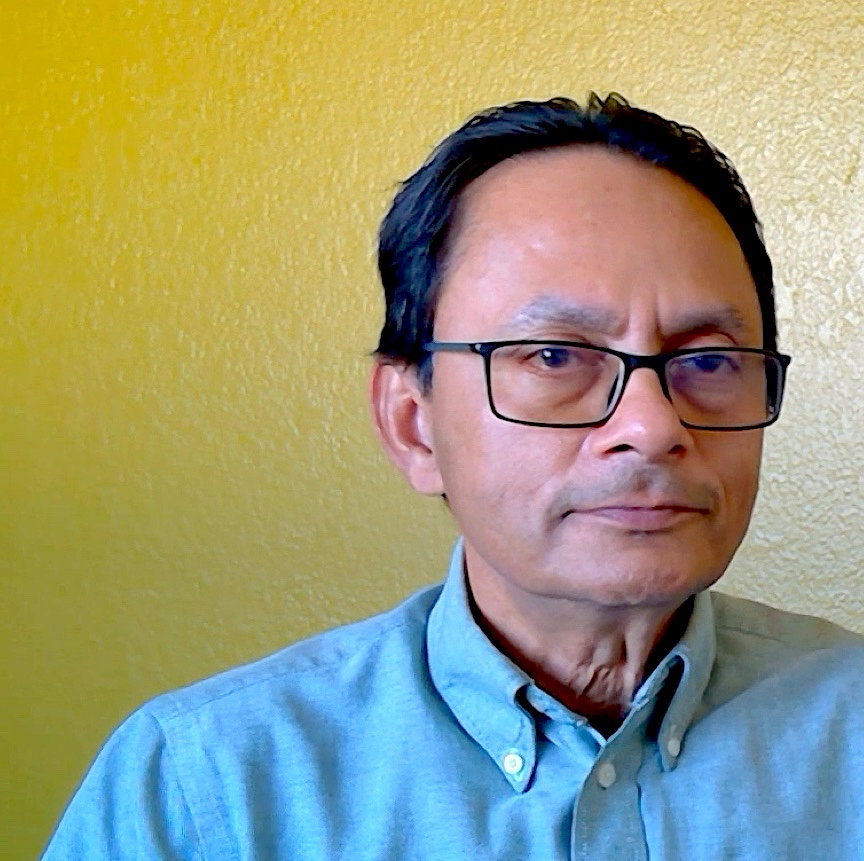

Arvind Kumar, San Jose, CA, 2021. OUTWORDS Archive.

Jiro Onuma (center) and friends, San Francisco, California. Courtesy of the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society

Author and activist Kiyoshi Kuromiya. Photo by Peter Lien.

“Willyce Kim.” Academy of American Poets.

Sources:

BlackPast. “(1970) Huey P. Newton, ‘The Women’s Liberation and Gay Liberation Movements.’” BlackPast.org, April 17, 2018. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/huey-p-newton-women-s-liberation-and-gay-liberation-movements/.

Braam, Ger van. Letter to Barbara Gittings. “Letter from Ger van Braam to Barbara Gittings.” Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library, November 9, 1964. https://qiarchive.org/en/lettersfromger/.

Brandt, Kate. “Willyce Kim: Reluctant Pioneer.” Essay. In Happy Endings: Lesbian Writers Talk About Their Lives And Work, 217–26. Tallahasee, Florida: Naiad Press, 1993.

Gadd, Christianne A. “The History of Esther Eng: Filmmaker, Restaurateur, Gender Rebel.” outhistory.org, 2016. https://outhistory.org/exhibits/show/esther-eng/essay.

Gittings, Barbara. Letter to Ger van Braam. “Letter from Barbara Gittings to Ger van Braam.” Manuscripts and Archives Division, the New York Public Library, October 29, 1964. https://qiarchive.org/en/lettersfromger/.

Gittings, Barbara. Letter to Ger van Braam. “Letter from Barbara Gittings to Ger van Braam.” Manuscripts and Archives Division, the New York Public Library, August 14, 1964. https://qiarchive.org/en/lettersfromger/.

Gittings, Barbara. Letter to Ger van Braam. “Letter from Barbara Gittings to Ger van Braam.” Manuscripts and Archives Division, the New York Public Library, April 25, 1964. https://qiarchive.org/en/lettersfromger/.

Gottschalk, Ryan. “Erased: An Exploration of Queer Japanese Americans’ Experience During the Internment Period.” eScholarship. Thesis, University of California, 2023. https://escholarship.org/content/qt9779n7nq/qt9779n7nq.pdf?t=s0vwfa.

“The Immigration Act of 1924 (The Johnson-Reed Act).” Milestones in the History of U.S. Foreign Relations. Accessed April 7, 2025. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1921-1936/immigration-act.

“July 4, 1965: First Annual Reminder Demonstration for Gay and Lesbian Rights.” Zinn Education Project, February 13, 2023. https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/first-annual-reminder-demonstration-for-lgbt-rights/.

Keehan, Owen. “Kiyoshi Kuromiya – Nominee.” Edited by Victor Salvo. Legacy Project Chicago. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://legacyprojectchicago.org/person/kiyoshi-kuromiya.

Kim, Eddie. “SF’s LGBTQ Chinese American Film Pioneer Broke All the Rules.” SF Gate, November 8, 2022. https://www.sfgate.com/streaming/article/sf-filmmaker-esther-eng-documentary-17564868.php.

Kim, Eunsong. “Unbinding Poetic Lives.” Poets.org, July 8, 2024. https://poets.org/text/unbinding-poetic-lives.

“KIM, Willyce.” Encyclopedia.com. Accessed April 22, 2025. https://www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/kim-willyce.

“Kiyoshi Kuromiya: From Selma Marcher to AIDS Activist.” NBCNews.com, March 8, 2015. https://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/selma-50th-anniversary/selma-marcher-aids-activist-life-steven-kuromiya-n318876.

Li-Anne. “Absences and Archives: Queer Asian (in)Visibilities and Histories.” North Carolina Asian Americans Together, August 5, 2021. https://ncaatogether.org/2021/08/05/absences-and-archives-queer-asian-invisibilities-and-histories/.

Marshall. “Japanese American Incarceration.” The National WWII Museum: New Orleans, July 11, 2018. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/japanese-american-incarceration.

Mukerjee, Lucy, and Arvind Kumar. Arvind Kumar. Other. OUTWORDS, December 10, 2021.

Paramasatya, Harits, Beau Newham, and Julia Winterflood. “Letters from Ger – A Digital Exhibition Exploring the Life of Ger van Braam.” Queer Indonesia Archive, July 10, 2023. https://qiarchive.org/en/lettersfromger/.

Roberts, Lj. “Looking for Jiro.” Hyphen, September 14, 2015. https://hyphenmagazine.com/magazine/issue-25-generation-spring-2012/online-exclusive-looking-jiro.

Stein, Marc, and Kiyoshi Kuromiya. Kiyoshi Kuromiya (1943-2000), Interviewed June 17, 1997. Other. Philadelphia LGBT History Project, 1940-1980. OutHistory, 2009.

Takemoto, Tina. “Jiro Onuma.” Densho Encyclopedia, June 22, 2020. https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Jiro%20Onuma/.

Takemoto, Tina. “Jiro Onuma.” Densho Encyclopedia, June 22, 2020. https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Jiro%20Onuma/.

Takemoto, Tina. “Looking for Jiro Onuma.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 20, no. 3 (June 1, 2014): 241–75. https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-2422665.

Thornton, Jacob, and Mark Otto. “Asian Pacific American Heritage Month 2024.” Asian & Pacific American Heritage Month. Accessed April 1, 2025. https://asianpacificheritage.gov/About.html.

van Braam, Ger van. Letter to Barbara Gittings. “Letter from Ger van Braam to Barbara Gittings.” Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library, May 8, 1964. https://qiarchive.org/en/lettersfromger/.

van Braam, Ger van. Letter to Barbara Gittings. “Letter from Ger van Braam to Barbara Gittings.” Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library, May 5, 1964. https://qiarchive.org/en/lettersfromger/.

van Braam, Ger van. Letter to Barbara Gittings. “Letter from Ger van Braam to Barbara Gittings.” Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library, November 9, 1964. https://qiarchive.org/en/lettersfromger/.

van Braam, Ger van. Letter to Barbara Gittings. “Letter from Ger van Braam to Barbara Gittings.” Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library, October 25, 1964. https://qiarchive.org/en/lettersfromger/.

van Braam, Ger van. Letter to Barbara Gittings. “Letter from Ger van Braam to Barbara Gittings.” Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library, August 25, 1964. https://qiarchive.org/en/lettersfromger/.

van Braam, Ger van. Letter to Barbara Gittings. “Letter from Ger van Braam to Barbara Gittings.” Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library, November 10, 1963. https://qiarchive.org/en/lettersfromger/.

Villemez, Jason. “Willyce Kim Wrote Her Own Story.” Pride Source, October 3, 2018. https://pridesource.com/article/willyce-kim-wrote-her-own-story.

Waxman, Olivia B. “Kiyoshi Kuromiya Helped AIDS Patients Get Life-Saving Info.” Time, October 21, 2021. https://time.com/6105139/kiyoshi-kuromiya-aids-activist/.

Wei, S. Louisa. “Esther Eng.” Women Film Pioneers Project, 2014. https://wfpp.columbia.edu/pioneer/esther-eng/.

Yang, Eric, and Philippe Plagbe. “Kiyoshi Kuromiya: Four Lessons in Human Rights Activism.” Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights, May 16, 2024. https://rfkhumanrights.org/our-voices/kiyoshi-kuromiya-four-lessons-in-human-rights-activism/.

Zhou, Li. “The Inadequacy of the Term ‘Asian American.’” Vox, May 5, 2021. https://www.vox.com/identities/22380197/asian-american-pacific-islander-aapi-heritage-anti-asian-hate-attacks.

Did that example spark some ideas for your museum or organization?

Let’s connect to make those ideas a reality! Book a Discovery Call today.