Queer people have always existed. However, the conversation surrounding how we talk about queer people in history is evolving.

What constitutes “proof” of a queer identity or relationship? What are the ethics of “outing” a historical figure? How do we leave room for queer possibility?

This three part series explores the challenges and opportunities of exploring queer history.

Part 2: Out of the Closet

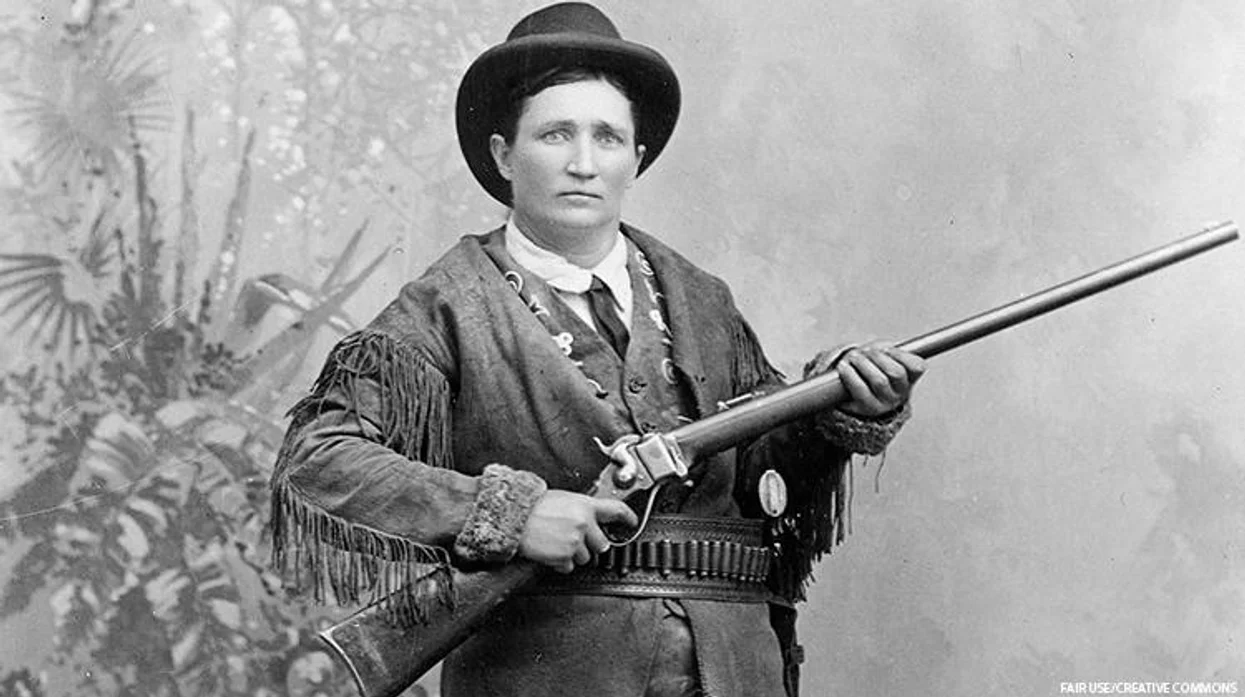

When the Washington State Historical Society developed the “Crossing Boundaries: Portraits of a Transgender West, 1860-1940” exhibit in 2021, the question of evidence was matched with an issue of ethics. In partnership with author Peter Boag, Head Exhibitions Coordinator Gwen Whiting began by revisiting the Society’s and other archives with a queer lens. Building off of the research Boag had compiled for his 2011 book “Re-Dressing America’s Frontier Past,” Whiting was on a mission to uncover more regional stories of gender non-conformity, particularly people of color. He wanted to combat the iconic stereotype of rigid gender norms of the “Wild West” and the notion that transgender and nonbinary identities are something new.

Given the intersectional identities of being gender non-conforming and non-White, the surviving materials of queer people of color were few and far between (see Note on Language). As a starting point, Whiting often turned to criminal records to learn of individuals who were punished for wearing “inappropriate clothing.” In many situations, personal journals and letters did not survive – or may have never existed – so it was unclear how someone truly identified.

In putting together this exhibit, Whiting had two concerns. First, is it ethical to “out” a historical figure and, secondly, how do we tell respectful stories when the source material is rooted in transphobia?

Whiting consulted with Boag and peers on both of these items. Sometimes she had information that made it clear that a historical figure lived openly as queer, but other times it was impossible to know. In some circumstances, the evidence simply doesn’t exist, but in others, someone may have not have been out due to safety. Further, words like “transgender” and “nonbinary” were not in use before 1940. Whiting considered how to tell an authentic queer story without putting historical figures into boxes based on today’s understanding of gender and sexual orientation. She elected to share the facts that are public knowledge and not prescribe modern labels to these individuals. She would share the historical evidence and explain how it connects to or echoes how we discuss queer identity today, so visitors could connect the past with the present.

It was also important to Whiting to elevate both queer joy and struggle in the exhibit. She considered how to strike a balance between sharing history in a way that was respectful without doing harm, such as using deadnames or only sharing stories of discrimination and punishment. Whiting was determined to share the sources she found, even those that may have included triggering experiences of discrimination and punishment or deadnames, with interpretation that provided a broader context. Though many of the stories were discovered using court records, Whiting was also able to reveal common experiences of queer people coming to the West because they saw an opportunity to start a new life or build accepting community.

In sharing the stories of gender non-confirming individuals, Whiting prioritized sharing known facts with compassion and respect for the individuals, regardless of how those facts may have been presented in primary sources. This often meant reading past transphobic or other discriminatory language in court cases and newspaper articles for the unbiased information and reinterpreting with dignity. In this way, Whiting was not sensationalizing these figures, but ethically sharing their truth to a contemporary audience.

Stay tuned for Part 3: Queer Possibility

Did that example spark some ideas for your museum or organization?

Let’s connect to make those ideas a reality! Book a Discovery Call today.

NOTE ON LANGUAGE: Our understanding of gender identity and sexual orientation has evolved over time. Some of the words we use today, like lesbian, transgender, or nonbinary, were not popular – or even existed – in certain periods of history.

I have elected to use the term “sapphic” to describe people who were perceived as women throughout the majority of their lives and had emotional and/or physical romantic relationships with other people who identified as women throughout a majority of their lives. This includes people who we may today understand as nonbinary or transmasculine, but identified or were perceived as women in their time.

Regarding people who may have been nonbinary or transgender in the contemporary understanding of gender identity, I use the word “gender non-confirming.” This includes people who were known to “cross dress” by wearing clothing considered appropriate for a gender other than that which they were assigned at birth. In some cases, these individuals were doing this to express their nonbinary or transgender gender identity, but may not always have been the case.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Baim, Tracy. “Sex, Love, and Relationships.” LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History. National Parks Service. 2016.

Biscoff, Libby. “The Mantle of Love and Friendship.” Historic New England, Fall 2018.

Daly, Marilyn Keith, Sam Dinnie, and Ali Kane, Case Study Interview, March 22, 2024.

Dinnie, Sam, Peter Gittleman, and Ali Kane. Case Study Interview, March 18, 2024

Hart, Ellen Louise, and Martha Nell Smith, eds. Open Me Carefully: Emily Dickinson’s Intimate Letters to Susan Huntington Dickinson. Ashfield, Massachusetts: Paris Press, 1998.

Kane, Ali, Sam Dinnie, and Gwen Whiting. Case Study Interview. Personal, February 27, 2024.

Kane, Ali, Sam Dinnie, and Gwen Whiting. Introductory Call. Personal, May 7, 2024.

Streitmatter, Rodger. “The Ethics of Historical Outing.” June 5, 2013. Beacon Broadside. https://www.beaconbroadside.com/broadside/2013/06/the-ethics-of-historical-outing.html

Turino, Kenneth C. “The Varied Telling of Queer History at Historic New England Sites.” Essay. In Interpreting LGBT History at Museums and Historic Sites, 131–39. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2014.